Production under solar panels

In France, photovoltaic (PV) greenhouses have appeared on the agricultural landscape in opportunistic fashion. When combined with agricultural activities, electricity production would appear a rather seductively virtuous solution. Many companies specialising in green energy production have offered partnerships to farmers (see box). There have been many attempts to grow crops under PV greenhouses, including with tomato, strawberry, raspberry, lettuces, etc. But capturing the light via photovoltaic panels and the shading this causes come at the expense of the luminosity available to the crops. “Our climate assessment and modelling work has shown a 46% decrease in light transmission under venlo-type PV greenhouses,” said Christine Poncet of INRAE Sophia Agrobiotech during an event dedicated to this topic in 2018. However, this light transmission depends on the design of the greenhouse, its orientation, its surface area, the rate of occultation (the exposed part is usually facing south, or 50% of the roof) and the transparency of the photovoltaic panels.

Problem-free harvest roll-out

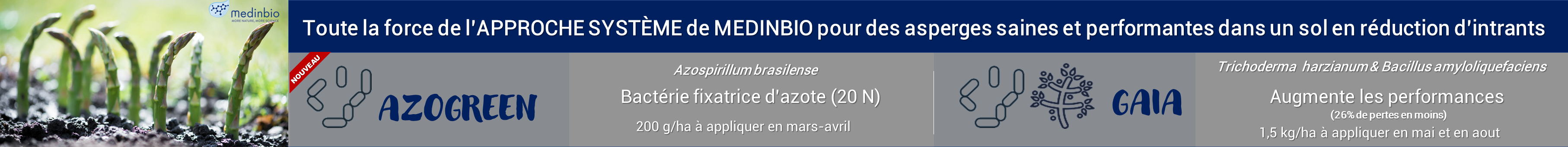

Cultivation and technical itinerary are equally important factors in ensuring successful photovoltaic greenhouse production. Asparagus is a crop that offers great potential as its production cycle seems to be well suited to the particular conditions of photovoltaic greenhouses. In fact, in the spring, the production of spears does not depend on the brightness of the shelter. The sun’s radiation alone can generate soil warming. At the end of harvest, the asparagus vegetation in the greenhouse receives enough brightness, which is at its maximum during the summer period. What’s more, the protection PV greenhouses offer from rain and wind, as well as part shading and the delaying of the first frosts seem to favour the development of foliage and longer storage. This is why several French asparagus producers have already committed themselves to this form of farming.

One such case is Régis Serres, a farmer in the Lauragais region (France). Today, he has a 10-hectare Reden Solar photovoltaic greenhouse park that is shared between asparagus and red kiwi production. He planted his first green asparagus in 2017. In the 2021 campaign, Régis Serres started the harvest on February 20th and had already harvested 2.5 tons by March 15th. As Serres explains, “Usually, the harvest runs from February 20 to May 25 and reaches about 4 tons per hectare. The harvest is smoothed out, with none of those production hits from the temperature variations that outside production is subject to.” This technology also provides the highest-quality asparagus. The greenhouse’s protected enclosure leads to a remarkably straight asparagus with excellent tip quality. “There is very little discarded at sorting – just 2%,” said Serres. The regularity of production also facilitates the commercial development of this high-end product, which is very popular with restaurant owners, even if this year’s pandemic has limited this segment of the market.

“Greater potential returns”

To obtain quality green asparagus, Régis Serres uses the Vitalim variety for its precocity and Grolim for its calibre. These varieties can obtain calibres of 16-22 mm and 22mm, respectively, as demanded by distributors. They are planted at a density of 10 plants per linear metre, in double rows, with an inter-row of 3.20m, or 35,000 plants per hectare. At the end of harvesting, the producer carries out light weeding and installs a drip irrigation system. The vegetation develops during the summer into four successive shoots that can reach up to 3m high. Régis Serres plans to top the first shoot at a height of 1m to avoid the shedding of vegetation. During this period, the plants’ health protection is limited to the use of an insecticide against aphids and asparagus beetle. There are no treatments used for foliage disease. The vegetation is halted by ceasing irrigation in early October, so that plants stop growing in mid-November, and the foliage turns yellow and dries out in December. The farmer grinds and removes the vegetation in mid-January. He then opens the greenhouse to allow the cold to plunge the crowns into vegetative rest for a few weeks. Régis Serres says that he is satisfied with his “production tool”, even though he thinks there is a potential for higher yields, albeit with slower growth of the asparagus. The producer and his team of pickers also appreciate the working conditions offered by this protected space. The various grinding and tillage work is always done on time and in good conditions, without the constraints associated with working in external environments. The convenience offered at harvest time is also very much appreciated. In addition, consumers love his asparagus, which not only looks better, but tastes better too.

Regularity and consistency of production

In the Landes region (France), Laurent Ginlardi also produces asparagus in a Mecojit photovoltaic greenhouse. He has 3 production sites of 2 ha. On two of his sites, the shelters are double-span greenhouses 2 x 6m wide and spaced 5m apart. This set-up allows for significant brightness.

Light enters through the sides and the opening facilitates ventilation. In 2017, Laurent Ginlardi

planted the Vitalim variety at 24,000 plants per hectare. Each span is planted with two rows 2.80m apart. The growing cycle is comparable to that employed by Régis Serres, but Laurent Ginlardi has chosen to produce white asparagus, which means the mounds are covered with black/white plastic. By keeping the greenhouses closed in early spring, the producer gains 1 to 2 weeks of precocity compared to field crops grown under a small plastic tunnel. He is also seeing regularity of production and homogeneity of calibres, which is advantageous for direct sales of his asparagus in the region’s various markets. “However, there is a difference between the row of asparagus most exposed to the sun and the others. Water requirements are higher and the quality of asparagus is lower,” said Ginlardi. In fact, he has observed a temperature variation of up to 10ºC between the sunny side of the greenhouse and the shaded side. Ginlardi, who also has another 2-hectare multi-span photovoltaic greenhouse, admits he no longer wants to produce asparagus in the field.

Buy-back deal entices producers

In France, like in Italy, the very attractive buy-back price of electricity has enabled the installation of a photovoltaic (PV) greenhouse park of several hundred hectares. And many projects are still underway, even though the feed-in tariff per kilowatt has dropped. In most cases, these are partnerships between energy producers and farmers. The former invests in the PV greenhouse and pockets the income from the sale of electricity, while the latter makes his land available for a period of 20 to 30 years and has the use of the greenhouse (not equipped), usually free of charge to ensure his agricultural activity over this period. This constitutes an enticing deal for producers, who get to have a “tool” without having to make the investment. The aim of the programme is to attract capital from non-agricultural sources. However, the findings and outcomes from various experimental trials (Ademe, INRAE, MAAP Working Group) tempered this enthusiasm somewhat due to the lack of light transmission in PV greenhouses caused by the covering of the south side in photovoltaic panels, often representing 50% of the roof. Experience has shown that not all vegetable species and production systems are economically viable and that crops should be adapted to these particular constraints.

Achieving brighter photovoltaic greenhouses

There are many types of photovoltaic greenhouses, and some poorly sized ones have too much shade. This penalises plant production and means that the structures are less productive. Faced with numerous failures, SDD Solar has developed a prototype photovoltaic greenhouse. Managers Philippe Dupouy and Hélène Dutrey said, “Our goal has been to make energy available to agriculture,”. Their 10 x 4.5m single-span greenhouse with channel was designed to achieve a compromise between power generation, brightness and ventilation. The photovoltaic panels are placed on the south side of 50% of the roof surface and achieve a light transmission of 20%. The rest of the cover is made of polycarbonate or glass. The sides of the greenhouse are closed using plastic films and insect-proof nets, thereby facilitating aeration and reducing the entry of pests. “The design of our greenhouses can be adapted to suit the crops envisaged. We want to be part of industry development projects alongside farmers,” said the SDD Solar managers. As part of a contract partnership, SDD Solar provides the greenhouse for agricultural production. According to the company, greenhouse development projects are underway in asparagus, kiwi, berries and vegetable crops in south-western France and abroad.